You Live, You Learn

- teodoratakacs

- Jul 29, 2021

- 18 min read

Updated: Jul 31, 2021

On a spring day in April 2011, I was preparing to leave the office for lunch, when I received an unannounced call from my boss. Do you have a few minutes? Sure, I said, trying to ignore the annoying hunger growls in my stomach. Can you go to another meeting room? There’s something I need to tell you. My stomach got from feeling hungry to feeling nervous, as my first thought was “something bad must have happened”.

My boss was letting me know that he was looking for a new product manager in the Belgium team. He thought I was a good fit for the job, so he asked me if I was interested. There was one condition though. I had to move to Belgium. My head was spinning while I was trying to remain calm and think things straight. It was the most difficult decision I had to make until that moment, with many pros and cons at the same time. On the personal side, the most important was to know that my mother was comfortable with my decision. On the professional side, I had doubts as high as mount Everest.

The product line I was going to manage was very technical and I knew that I had big shoes to fill. I made a list of everything I had to learn: product operation, features and benefits, differentiators, market positioning, applications, customers, electromagnetism, electronics, camera technology, market trends and competition. It was going to take years to learn and bring some added value. I had no engineering background, no previous experience with that product segment and little experience with anything overall. I was an impostor, couldn’t everyone see it?

So, I said yes. What else? On a hot day of July, I packed my stuff and moved 2.000 km away. Little did I know that most of the things I was going to learn the following years, were not on my list: living in a new country, learning a new language, understand the new culture and meeting new people.

I was 29 and said yes to a new life adventure, where change and learning became the two constants in my life.

******

I have always been a learner, like we all are, just in different concentrations. Some of us learn by reading, others by socializing or by being involved in diverse experiences. And others learn by just being who they are and living their life day by day. But how many times do we stop and actively think: what did I learn from this? What does it mean to effectively learn and get the best of that experience? What are the key success factors of effective learning?

These are questions that kept me busy for many years, as I was looking for ways to support my team to learn and develop better skills and as I was supporting my son in his learning journey. But most of all, because I was interested in developing better learning skills for myself. As I wrote earlier, learning is not enough and it doesn’t always bring development and growth, when the focus is put in the wrong place. Especially if we don’t find ways to apply what we learn in our daily life.

I often get this question from people who moved to a different country and try to integrate to the new culture: How did you manage to learn Dutch? It seems like an impossible language. I also followed this and that course but for some reason it doesn’t stick. There is always an assumed reason why: I am just not good at languages; the course material was too theoretical; I had a bad teacher; I didn’t have enough time to study; the course was too late in the evening; the course was too early in the morning; the course was on Friday 13 or on a full moon day. You get the idea. Then I ask them: and how did you practice this new language, in what context were you speaking it? Well, I wasn’t. I didn’t feel comfortable, I was afraid I would be judged, my level was just not good enough to even try to speak it.

People often look at the result of a learning process and they compare themselves to that. But they forget to ask how much time and effort it took to get there and how the journey looked like. In my case with Dutch, it took three to four years of continuous learning in different formats: online courses (6 months), weekend classes (12 months), evening classes (24 months), speaking with family members and neighbors and later when I became a mother, practicing daily at the day care, pharmacy, doctors and with other parents (years and years).

The worse thing that we can do is to compare ourselves as beginners, to someone who is proficient in a certain skill. That can demotivate us immediately because the gap is scary. But we need to keep in mind that even the most expert of the experts, was a beginner at some point and stood exactly where we stand right now. No skill or extraordinary achievement happened overnight. So instead of comparing, we need to understand and demystify the process. But wait, where do I even start?

Start With Why

There is a big difference between learning because we want to and learning because we must. When we must learn something, it is usually in a context of formal learning, with the purpose of getting a certification and formal acknowledgement of our competencies. It could be that our boss sent us to a training to improve our negotiation skills, or that our parents sent us to private English classes, or that we simply had to learn a secondary skill to be better in our main profession. It doesn’t always mean that if we must learn something we are less motivated, or that it will be more difficult to find the drive and the focus.

But it is important to constantly ask ourselves why we are learning that skill and how it will help us long term. If we don’t find meaning in what we learn, it will be very difficult to sustain the effort and get results.

On the other hand, when we decide what we want to learn, the decision process can get tricky. Even when we have enough intrinsic motivation at start, if we don’t spend enough time assessing why we need to learn that specific skill, we might find ourselves giving up halfway. Talking from my personal experience, I found myself many times jumping impulsively on an online course, just to realize two weeks later that I didn’t need that course at that moment in my life. The idea of knowing more is attractive and mesmerizing, but often unnecessary.

Choosing what we learn, starts with identifying a few gaps:

1. Knowledge Gaps

Sometimes we need information and theoretical knowledge to learn how to perform a certain action in the future. But learning for knowledge, doesn’t mean just accumulating information. It means knowing what to do with it, and when to use it. It’s less about memorizing information that you can easily retrieve, but more about knowing how to organize that information, so you can find it back and use it whenever you need it. Knowledge alone is rarely enough in order to achieve competency in a certain area. It’s knowing how to strategically apply that knowledge that builds a new skill and makes you competent.

2. Skill Gaps

Any skill implies some theoretical knowledge, but there is one element that differentiates skill from knowledge: practice. Take any activity or profession you want, and you’ll see that knowing the entire literature on a particular subject, will not make you an expert unless you practice it. There is one simple question you can ask, to determine if the gap is knowledge or skill: is it reasonable to believe that I can be proficient at this without practicing?

3. Motivation Gaps

Assessing our motivation is probably the most important element in our learning journey. Many people start learning without thinking thoroughly about their motivation and they end up giving up halfway. Maybe they didn’t really believe in the destination, or they were lacking the big picture. Maybe they didn’t expect so much change, or they got distracted on the way. Or maybe they just didn’t want to put so much effort. Any learning process involves obstacles, difficulties and new challenges that make our brain uneasy and restless. Are you determined enough to overcome these obstacles? Our brain wants it easy, wants the shortcut and the automatism and therefore the habit gaps are the next important gaps to identify.

4. Habit Gaps

When I wanted to learn how to meditate, I realized that the gap between where I was and where I wanted to be, involved creating a habit. Without developing a daily habit of deliberate practice, my brain was always focusing on doing something else, something easier. Most of the times it involved something with food. I am struggling with the same resistance when it comes to writing, and I am working hard to create a new habit of writing every day, until I get to the point where it doesn’t feel so hard to do. Habits don’t form overnight, and they are even more challenging when you need to unlearn certain things or to replace a habit with a new one.

5. Environment Gaps

You want to be proficient in Japanese, but you live in Germany, have no Japanese friends or family, no Japanese TV channels and no internet to listen to Japanese people talking on YouTube. Good luck learning Japanese! Or let’s say you want to learn how to work with Photoshop, but you have a computer that doesn’t support the latest version and crashes in the middle of your project. The environment you live and work in, needs to support what you are trying and learn and practice. If it doesn’t, you need to make it happen.

6. Communication Gaps

What type of communication do you require to learn effectively? It can be the communication with the teacher or trainer, with your peers, with family or friends. Are the goals well communicated and understood by all the parties? Is the ongoing communication during the learning process supporting what you try to achieve? Communication is two ways, and it involves receiving and giving feedback, so we should think right from the start how we envision to make this happen throughout the learning process.

Are You a Reader or a Listener?

When I read Peter Drucker’s piece on Managing Oneself a few years ago, I was struck to realize that I had never thought about how I learned. Was I a reader or a listener? We all have an innate preference and it’s debatable if we need to stick to it or try to develop alternative styles. It’s like being a right-handed person trying to learn to be ambidextrous. It could be useful in case you break your right arm, but then, how often could that happen? And what’s the worst thing that can happen if you can’t write for a few weeks? Is the effort paying off or is it better to stick to what comes naturally to you?

I am a writer when it comes to how I process information and how I prepare for a presentation. That means I need to write down the main ideas, define the flow and rehearse based on that structure. When I talk about a topic, I visualize the written overview, even if I don’t memorize all the details. This is also how I learn. I need to write down my thoughts, reformulate ideas in my own words and then read them again out loud.

On the other hand, someone who is a listener, can process thoughts and information by hearing and talking. For example, if I am a listener and want to rehearse for a presentation, I will call a friend and talk to him for half an hour, to clarify my main ideas and get feedback.

Once we understand our preference and what works best for us, we can of course experiment with other ways and start expanding our comfort zone. I know my preference is to read and write, but this also has some disadvantages in the high-speed world we live in. It takes more time. So, I deliberately started to use alternative methods like listening to audio books and Podcasts and summarizing them by recording myself on the smartphone. It is incredibly hard, and I must force myself to do it, but I notice the progress and I feel it becomes a little easier every time.

If you are a listener, but want to experiment with writing, I recommend doing the same. Try to force yourself to write five things about what you have learned, at the end of each chapter or learning milestone. Even if you never go back to read what you wrote, the simple fact that you put effort in it, it will help you retain information long term.

Whether you are a listener or a reader, what makes learning effective is deep practice. Daniel Coyle talks about this in his book The Talent Code and he gives a very simple example to start with.

Let’s do this experiment. Have a look at the word pairs below and try to memorize as many pairs as you can.

Now take a paper and write down the ones you can remember. How many did you remember from column A? How about from column B? The reason why you remember more from column B is that your brain had to stop for a millisecond.

Having a small obstacle and struggling with something, makes us smarter.

I often experience this when driving to a new destination. If someone else is driving, I don’t really pay attention to all the signs and even when I look out the window, I see the landscape or the sky, and not the signs. So, if you ask me what route we took to get there, I will have no idea. It’s different when I drive, but even then, if I rely too much on the GPS and I don’t stop and think, I might end up like that woman who went to pick up her friend from the train station in Brussels and ended up in Croatia.

Break Down and Integrate

As I was curious to know more about different learning strategies, I talked to Adelina Pavelescu who is both a learner, preparing for an important exam later this year, and a fellow Change strategist, coaching students and educators to become more effective and develop better learning and teaching skills. I wanted to understand in what way formal learning is different from life-long learning and what are the success factors if we want to learn and retain information for the long term.

One important element, whether we talk about learning for an exam or learning to develop a new skill, is to start from evaluating what we need to learn and make a plan. Very often, people are overwhelmed by the volume of the learning material, diversity of sources and many unknowns that come with the process. So, they get blocked. Ideally, the trainer or the teacher gives some guidance about what and how much you should learn every week. But it rarely happens. Plus, everybody learns in different ways.

If you are someone who needs to learn independently and doesn’t get a lot of guidance, a good place to start is to take a sheet of paper and a pen and make a timeline. How much time can you allocate each day for learning and practicing? Once you defined your timeline, start breaking down the material into manageable chunks and commit to study the assigned batch every day or on the planned days.

Planning and discipline are key ingredients for effective learning. But even more important is to acknowledge progress and celebrate the small wins.

This can be already integrated in your plan. When you finish a book, a module or the first three chapters, get yourself a small reward. It doesn’t have to be an ice cream. It can also be a chocolate chip cookie…

Another essential aspect is that we need to find ways to integrate what we learn into our daily schedule and embed the learning process into our routines. One of Adelina’s clients was a biology teacher, young mother of two, preparing for an important and difficult exam. While she was very determined and motivated, she had a busy schedule and was overwhelmed with family responsibilities throughout the whole day. At 10PM when she was done with everything, she wanted to start studying. It was impossible. Tiredness and lack of focus kicked in, every single time. So, it wasn’t until she started to integrate the study material in her daily activities, that she managed to see progress. This was as simple as explaining to her toddler what the functions of the heart were, while the kid was drawing a heart. Or reading out loud and recording a lesson and then listening to it while she was driving to the supermarket or washing the dishes.

There are three essential questions that Adelina would ask before deciding to follow a new program or training:

1. How does this program help me on the long term? Where does it fit in my learning goals and professional plans?

2. Can I trust the trainer delivering this course? Does s/he have good recommendations from people I know and trust?

3. Will learning this new subject or skill make my life better? Does it help me in other areas of my life?

If you answer yes to all three, then you’d better hurry. You have some cool stuff to learn about.

Learning Fast and Slow

One of the most important questions besides why we learn, is do we want to learn for a short-term goal, or do we learn for the long term? This also depends of course on what we are learning. There are certain skills that we can learn in a two-day course and immediately apply, like making bread or creating origami, but there are skills and competencies that take months or years and require a thorough learning plan and trajectory, where each learning block builds on the previous one to develop a more complex skill.

Think about problem solving, business insights or financial management. These are not competencies you can learn and develop in one course.

So, when you enroll in a learning program, go back to the gaps, ask again why and then make a list of actions that would signal proficiency in that area.

For example, let’s say I am thinking to enroll to a German class. This is my checklist before deciding to enroll:

What I can immediately say after reviewing my list is that my intrinsic motivation is low, and the effort required will be high. Knowing that I am already very busy, and my schedule is packed, there is a clear risk that I will give up before I get the skill level I desire. However, the fact that I don’t have big environment gaps and I would have daily opportunities to practice what I learn, could get me more motivation during the process. Appetite comes with eating. So, I decide to start the German course and make a learning plan that would involve acquiring the right vocabulary that would allow me to speak and write in German in daily contexts.

In my role as manager, it’s my responsibility to support my team in developing better competencies and learning new skills. But I don’t believe that sending people to trainings or giving them access to LinkedIn Learning is the answer to their development. Unless the training is part of a long-term development plan and builds on an existing foundation, the only thing you will get is some additional tool, technique or concept. But to develop core competencies that create a strong foundation for development, online courses are not the answer.

Stewart Brand is the founder of the Long Now Foundation, a project born out of a need to provide a counterpoint to today's accelerating culture and help make long-term thinking more common. He is also the author of How Buildings Learn: What Happens After They’re Built. In his view, some things change quickly (the decorations, the furniture, or the plants in a house), some things change more slowly (the layout and structure of the house) and some things change very slowly (the foundation).

The same applies to the learning pace when we learn to build a foundation, we learn for skills, or we learn for tools and techniques. We should not start with the tools, while there is no foundation in place. The foundation means our core values, our character traits and our identity. It’s an inside out approach. If you want to become a gardener, start thinking about yourself as being a gardener before you invest in expensive gardening equipment. Start with knowing yourself, your motivations, your aspirations, your likes, and dislikes, then work on skills and attitudes, and only then work on tools and techniques.

How Much Do We Retain?

When we process any type of information, we automatically rely on our memory. But on which memory? Every time we see, hear or feel something, whether is the sight of the sunset, the sound of the piano, the smell of coffee, or raindrops on our skin, these bits of information are stored for a short time in our sensory memory. These are things that come and go and will not get stored for a long time, unless we pay attention, or we intentionally look for them. I sometimes enjoy a moment so deeply that I want to capture it and store it for long term. Then I usually write down what I felt, or I just describe it to someone. That’s the only way that works for me.

Once we pay attention to something, it enters our short-term memory that can keep items for a bit longer, but it has a limited capacity. Maybe you’ve heard about the magical number seven, plus or minus two, the concept that George Miller launched in 1954, to prove that we humans, are only capable to remember 5-9 things at any given time, without resorting to techniques like chunking and separating into categories.

But how do we keep things in the long-term memory? If you try to visualize your memory like a closet, is it nicely organized by category or color? Is it a KonMari style closet, or rather a go-with-the-flow, I’ll-pick-what-comes-handy type of closet? When we work with categories or associations, it’s easier for our brain to retrieve the information every time it needs it. Keep the shelves organized, be mindful of what you keep, and make sure you use often what you want to keep.

To learn in the same context and environment in which we apply the learning, or to explain it and teach it to someone else, are techniques that support long term learning.

For me personally, the thing that works best is to write down main ideas and build mind maps summarizing the structure of the material I want to remember. Especially for writing, I need to make connections between ideas and concepts I read in multiple books and be able to easily find back stories I liked. Mind maps save me a lot of time and bring me peace of mind. When I read books, I like to create one overview with the structure of the book, because I can follow the storyline easier. Then, for each part or chapter, I write down some key concepts, stories or names that made an impression on me and I want to either research further, or just go back from time to time.

Learn With the Goal of Teaching

Learning with the goal of sharing or teaching is probably one of most efficient ways of learning. When you learn in order to teach, you process information in a different way. You’re consuming information in order to transform it into something new. You extract the essence, you think about why it is important, and you explain how something works, in your own words.

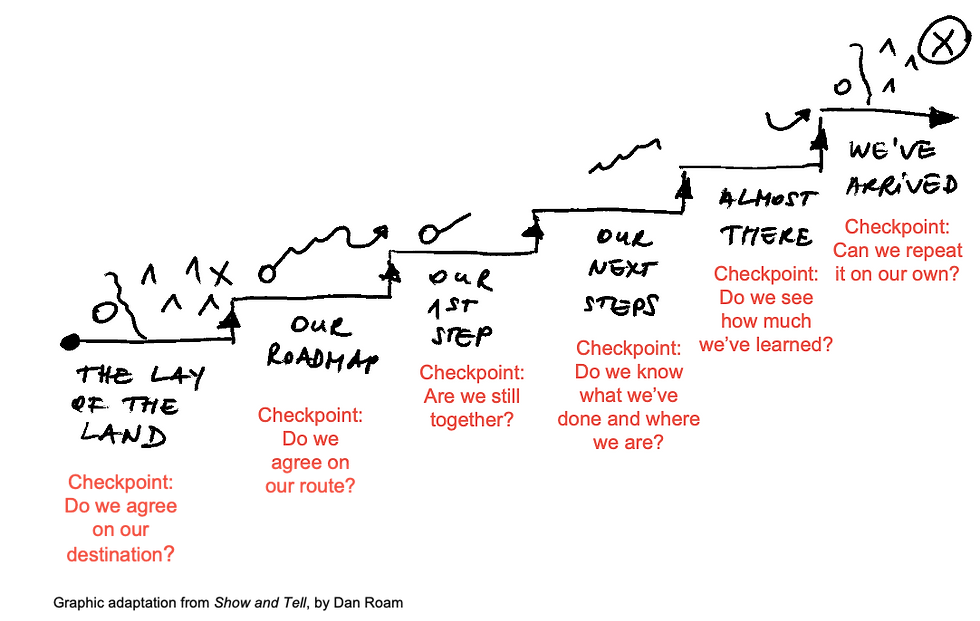

When I was learning about how to deliver better presentations, I came across one of the best how to books I’ve ever read: Show and Tell, by Dan Roam. It shows with very simple and minimalist drawings, how to build a good explanation.

When I learn something and I want to memorize main ideas for the long term, I remember that any explanation takes us to a new level of understanding, but a great explanation makes it effortless.

As you build your argumentation and explain to someone how to get from one point to the other, stop and reflect on the checkpoints.

Alexandra Mihai is a good friend of mine and Assistant Professor of Innovation in Higher Education at the University of Maastricht, researching and teaching learning design. Normally we talk about food and baking, and we share recipes of tarts and cupcakes, but last month we met and talked about learning tips and tricks. From her years of experience in designing online learning programs and teaching, she summarized a few guiding principles that could help someone get unstuck when feeling overwhelmed or demotivated.

Use this as a checklist before you embark in a learning journey or when you are navigating unknown waters and find yourself thinking “what I am doing here?”

1. Always start with setting an intention and reflect on why you want to learn something. Most of the times, it serves a long-term goal or aspiration, so try to focus on that and imagine how it will feel when you get there.

2. Assess the material you need to learn, organize it and break it down into chunks. Think about learning as playing with Lego. You build separate sections that will connect and build on each other.

3. Block time in your calendar and commit to those timeframes. Focus is hard, but it pays off. So, create the right environment that help you limit distractions.

4. Find a study buddy and find opportunities to connect and learn from others.

5. Share what you learn or explain it to someone else like you would teach it.

6. When you have a choice, always choose an instructor-led program, even if it’s online, then just a pure online mass audience course.

7. Find opportunities to ask as many questions as you can.

8. Context is everything. Learn in the context in which you will be using that skill. The brain makes better connections and associations long term, where there are cues and anchors you can go back to. Most skills that require practice, should be learned in the environment in which they will be applied.

9. Talk to someone who already has the skill you want to achieve. How did they get there? What was their learning path? What would they have done differently?

10. Take breaks and leave enough space in between learning sessions. Your brain needs time to process and make connections so don’t try to accumulate too much information in a short time because it will be counterproductive.

It’s been exactly ten years since I moved to Belgium and this picture was taken while I was driving to my new home. I got lost somewhere in Germany, but it felt like I got lost in this world. So many unknown signs, no clear direction, so many questions and people answering in languages I didn’t understand. But I kept driving. And I kept asking.

When I think about everything I learned throughout the years, without having a clue what I was doing and how I was learning, I sometimes think “what a waste of time”. So much stuff that I read and spent time on, without needing it or using it. I jumped on so many trainings that didn’t bring any added value, because I just didn’t really need that information. But then, when I stop and reflect a bit deeper, I realize there are indirect connections that formed and that did help me in other areas I focused. If I look back at the last decade, there hasn’t been one year that resembled the other. Every year brought some changes, in my work and in my personal life. And the only other constant besides change, was learning. You live, you learn.

Recommended And Mentioned Resources:

Read

Design For How People Learn, by Julie Dirksen

Managing Oneself, by Peter F. Drucker

Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World, by David Epstein

How Buildings Learn: What Happens After They’re Built, by Stewart Brant Watch

How to Remember What Your Read, Tim Ferriss

Listen To

When Everything Clicks: The Power Of Judgment-Free Learning, Hidden Brain, with Shankar Vedantam.

If you liked this article and it helped you in any way, share it with a friend and subscribe to my newsletter for a monthly dose of drive and inspiration.

To ask me a question or schedule a short phone call, please send me an email at heysparkingdrive@gmail.com.

Comments